|

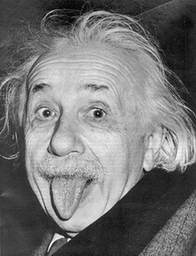

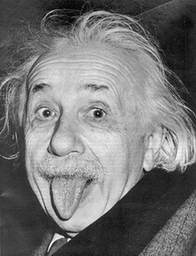

Религиозные взгляды Эйнштейна являются предметом давнишних

противоречий. Некоторые

авторы и комментаторы утверждали, что Эйнштейн верил в существование бога; другие говорили,

что он был атеистом. И те, и другие использовали и используют для подтверждения своей

точки зрения различные слова великого ученого. Сомнительно, что согласие в этом вопросе

будет достигнуто в скором будущем.

Религиозные взгляды Эйнштейна являются предметом давнишних

противоречий. Некоторые

авторы и комментаторы утверждали, что Эйнштейн верил в существование бога; другие говорили,

что он был атеистом. И те, и другие использовали и используют для подтверждения своей

точки зрения различные слова великого ученого. Сомнительно, что согласие в этом вопросе

будет достигнуто в скором будущем.

Тщательное рассмотрение того, что говорил Эйнштейн о своих взглядах

на религию, показывает, что мировоззрение гениального ученого невозможно уместить в

стандартные схемы, тяготеющие к делению на черное и белое. Те, кто полагают, что

Эйнштейн верил в существование бога, справедливо отмечают, что сам Эйнштейн говорил,

что он религиозен и что он верит в бога. Однако они пропускают тот факт, что Эйнштейн

подразумевал под "богом", "верой в бога" и "религиозностью" совсем не то, что

подразумевают верующие иудеи, мусульмане, христиане и представители многих других

религий, а также множество официальных церквей (вроде Католической церкви, Англиканской

или Русской православной церкви). Действительно, сам Эйнштейн написал, что, "с точки

зрения иезуитского священника я, конечно, атеист". Подробнее

см. здесь.

Я включил Эйнштейна как агностика в этот перечень атеистов на

основании следующих фактов.

Он утверждал, что не верит в персонифицированного бога.

Он написал одному адресату, что его можно назвать агностиком.

Но он не желал называть себя атеистом.

Ниже приводятся цитаты, на которых базируются приведенные

заключения.

от 24 апреля 1929.

Эта цитата появилась после того, как теория относительности

была подвергнута критике с религиозных позиций. Это побудило раввина Нью-Йоркской

синагоги Герберта Гольдштейна (Herbert Goldstein) послать Эйнштейну телеграмму, чтобы

спросить ученого, верит ли он в бога. Текст телеграммы гласил: "Do you believe in God?"

Эйнштейн ответил:

"I believe in Spinoza's God who reveals himself in the orderly harmony

of what exists, not in a God who concerns himself with fates and

actions of human beings".

Из письма от 24 апреля 1954.

22 апреля незнакомый Эйнштейну человек, назвавший себя атеистом, послал

ему длинное письмо, в котором в частности выражал сомнение в достоверности статьи

о религиозных взглядах Эйнштейна, которую он читал. Эйнштейн ответил по-английски:

"I get hundreds and hundreds of letters but seldom one so interesting

as yours. I believe that your opinions about our society are quite reasonable. It

was, of course, a lie what you read about my religious convictions, a lie which is

being systematically repeated. I do not believe in a personal God and I have never

denied this but have expressed it clearly. If something is in me which can be called

religious then it is the unbounded admiration for the structure of the world so far

as our science can reveal it. I have no possibility to bring the money you sent me to

the appropriate receiver. I return it therefore in recognition of your good heart and

intention. Your letter shows me also that wisdom is not a product of schooling but of

the lifelong attempt to acquire it".

Перевод выделенного фрагмента:

"Это была, конечно, ложь - то, что вы читали о моих

религиозных убеждениях, ложь, которая систематически повторяется. Я не верю в

персонифицированного бога (personal God), и я никогда не отрицал этого, но выразил

это отчетливо. Если во мне есть что-то, что можно назвать религиозным, то это только

безграничное восхищение устройством мира, насколько наша наука способна

его постичь".

В 1950 году некто по имени Гай Ренер (Guy H. Raner) обратился

с письмом к Эйнштейну, прося еще раз разъяснить его взгляды по вопросу существования

бога. Он написал:

"Some people might interpret (your letter) to mean that

to a Jesuit priest, anyone not a Roman Catholic is an atheist, and that you are in fact

an orthodox Jew, or a Deist, or something else. Did you mean to leave room for such an

interpretation, or are you from the view-point of the dictionary an atheist; i.e.,

"one who disbelieves in the existence of a God, or a Supreme Being?"

Эйнштейн ответил в письме:

"From the viewpoint of a Jesuit priest I am, of course, and have always been

an atheist. ... I have repeatedly said that in my opinion the idea of a personal

God is a childlike one. You may call me an agnostic, but I do not share the crusading

spirit of the professional atheist whose fervor is mostly due to a painful act of

liberation from the fetters of religious indoctrination received in youth. I prefer

an attitude of humility corresponding to the weakness of our intellectual understanding

of nature and of our being". (Акцент добавлен автором WEB-страницы).

Отрывок из письма Альберта Эйнштейна Морису Соловину от 1

января 1951 года:

"Мне вполне понятно Ваше упорное нежелание пользоваться

словом "религия" в тех случаях, когда речь идет о некотором эмоционально-психическом

складе, наиболее отчетливо проявившемся у Спинозы. Однако я не могу найти выражения

лучше, чем "религия", для обозначения веры в рациональную природу реальности,

по крайней мере, той ее части, которая доступна человеческому сознанию. Там, где

отсутствует это чувство, наука вырождается в бесплодную эмпирию. Какого черта мне

беспокоиться, наживают ли попы на этом капитал. От этого все равно нет

лекарства..."

В "Автобиографических заметках" Эйнштейн написал следующее

об эволюции его взглядов на некоторые вопросы религии:

"Thus I came - despite the fact I was the son of entirely

irreligious (Jewish) parents - to a deep religiosity, which, however, found an abrupt

ending et the age of 12. Through the reading of popular scientific books I soon

reached the conviction that much in the stories of the Bible could not be true.

The consequence was a positively fanatic [orgy of] freethinking coupled with the

impression that youth is intentionally teeing deceived. ... Suspicion against every

kind of authority grew out of this experience, a skeptical attitude. ... which has

never left me..."

Из письма, написанного изначально по-немецки:

"I cannot conceive of a personal God who would directly

influence the actions of individuals, or would directly sit in judgment on creatures

of his own creation. I cannot do this in spite of the fact that mechanistic causality

has, to a certain extent, been placed in doubt by modern science. My religiosity

consists in a humble admiration of the infinitely superior spirit that reveals itself

in the little that we, with our weak and transitory understanding, can comprehend of

reality. Morality is of the highest importance-but for us, not for God".

Из письма чикагскому раввину о предполагаемых религиозных значениях

теории относительности:

"I do not believe that the basic ideas of the theory

of relativity can lay claim to a relationship with the religious sphere that is

different from that of scientific knowledge in general. I see this connection in

the fact that profound interrelationships in the objective world can be comprehended

through simple logical concepts. To be sure, in the theory of relativity this is

the case in particularly full measure. The religious feeling engendered by experiencing

the logical comprehensibility of profound interrelations is of a somewhat different

sort from the feeling that one usually calls religious. It is more a feeling of awe

at the scheme that is manifested in the material universe. It does not lead us to

take the step of fashioning a god-like being in our own image - a personage who

makes demands of us and who takes an interest in us as individuals. There is in

this neither a will nor a goal, nor a must, but only sheer being. For this reason,

people of our type see in morality a purely human matter, albeit the most important

in the human sphere".

This quote from Einstein appears in "Science, Philosophy,

and Religion, A Symposium", published by the Conference on Science, Philosophy

and Religion in Their Relation to the Democratic Way of Life, Inc., New York, 1941.

"The more a man is imbued with the ordered regularity of

all events the firmer becomes his conviction that there is no room left by the side of

this ordered regularity for causes of a different nature. For him neither the rule of

human nor the rule of divine will exists as an independent cause of natural events.

To be sure, the doctrine of a personal God interfering with natural events could never

be refuted [italics his], in the real sense, by science, for this doctrine can always

take refuge in those domains in which scientific knowledge has not yet been able to

set foot. But I am convinced that such behavior on the part of representatives of

religion would not only be unworthy but also fatal. For a doctrine which is to

maintain itself not in clear light but only in the dark, will of necessity lose

its effect on mankind, with incalculable harm to human progress. In their struggle

for the ethical good, teachers of religion must have the stature to give up the

doctrine of a personal God, that is, give up that source of fear and hope which

in the past placed such vast power in the hands of priests. In their labors they

will have to avail themselves of those forces which are capable of cultivating the

Good, the True, and the Beautiful in humanity itself. This is, to be sure, a more

difficult but an incomparably more worthy task".

"A man's ethical behavior should be based effectually on

sympathy, education and social ties and needs; no religious basis is necessary.

Man would indeed be in a poor way if he had to be restrained by fear of punishment

and hope of reward after death."

|